By MSc Gvapo Tripinovic

An extended topic for a complicated and sensitive matter. Most parents follow the one dollar per day rule, meaning I should give my eight-year-old son 7 dollars per week.

On popular Quora ((9) Search (quora.com)), like on many other websites, you can find many answers about the same or different sum the children deserve to have. Sum usually depends on where you live, financial status, social status, and even the religion someone belongs to. I have seen hot debates on this topic online and while talking to other parents.

The majority agrees that young kids should get some allowance and that parents should take care of children’s needs. Occasionally provide some “bonus sums” if they find their children’s requests moderate and relevant or if children achieved something remarkable.

Answers vary from those who think children should get more to those who have an opinion that children don’t understand anything about money.

These answers were not what I was looking for. Five years ago, my Adam was a toddler. As any proud and happy dad with solid financial standing, I wanted to buy him everything I could. To see him happy, to see him smile. I understood before he was four that I was doing things very wrong. My son didn’t enjoy the things we were buying that much, as he barely looked at them once we arrived home. He was enjoying the shopping, not the stuff we were buying. It was funny initially, but it became disturbing within weeks of my realization. Not to mention that buying things you don’t need is becoming expensive and pointless.

My first reaction was to stop buying all these things, but going to the mall, or any other shop, was becoming quite difficult. We are talking about a toddler who used to get something each time we went out.

My second strategy was that we start gathering all the least loved toys and then give them to those in need. It was a great feeling, and soon our flat became larger with much more free space. Yet, we did not solve the core problem.

My dear, generous Adam wanted to help all the kids and give them something. It was not important if they already had something or not. He just wanted to give them presents to make people around him happy. Everyone complimented him on how good he is, how unselfish his actions are, and how he puts other kids’ needs before his own.

Although all that was very nice initially, we were still spending a crazy amount of money in accomplish my son’s new mission of helping the world. Excellent idea, but not sustainable and not solving the core problem.

I could stop buying things, but that would not solve the problem. That would only let it pop up on other occasions when it would be harder to handle.

I spoke with other parents about the issue. Everyone agreed that it would be great if the kids understood the real value of the money and how hard it is to earn them, but they are just way too small at the age of 4 – 6 years to understand that. They don’t know the numbers and calculus, they don’t know to read, and they don’t understand what it means to work.

I nodded in agreement, but I started searching the internet. I found some great content, which has been updated since, on: Should children get pocket money? | OneFamily, Pocket Money: How To Help Your Child Learn About Money – N26, Pocket Money & Kids ¦ Advice for Parents – SchoolDays.ie, and many articles on https://theconversation.com.

All that persuaded me to apply something new and test that new knowledge. My son was yet to turn 4. As usual, we went to the mall, and I asked him to look at small numbers (price tags) on the toys we had seen. The better the toy is, the larger the number is. That was interesting, so we played. We tried to find toys with the smallest and largest numbers. Later, at home, I asked him which toys he liked more — the ones with the small numbers or large numbers. The answer was that he mainly liked the one with the large numbers (robots, high-quality toys from reputable producers, Lego, large toys…). Not long after, I started teaching him numbers. From 1 to 10. Testing occurred in the shops, where he could soon identify numbers from 0 to 9 in each place he could see.

When we returned home, I was satisfied thinking about the dozens of articles I had read on this topic, but something was still missing. Most of the essays and papers didn’t go further than answering: “What do I expect my child to buy with that allowance?” That was a good way of thinking forward but not good enough. I wrestled in my head if I was taking this way too seriously. I could not sit still, so I decided to experiment.

Later that day, I gave him some money. He was puzzled and asked why and what he should do with that. I explained that he had earned that money, and now it belonged to him. His work was learning the numbers, and if he did more “smart and other skillful things,” he could earn more. Not long after, he returned thoughtfully and said, all business, that he liked the idea and needed us to define what other things he could do to earn more. How can he know how much he is making, how much he has earned in total, so he can buy something he likes? This was toddler speaking!

I grabbed the opportunity to try something wild. Now thinking that was not such a great idea, but at that moment, I thought it was something fun.

I told my toddler son that he would have new toys only on three occasions: for his birthday, for Christmas, and when he does something exceptional and he should be rewarded. If he wanted something more, he would need to use the money he earned.

It proved to be an interesting and very defining moment. My not yet full four-year-old boy has started learning the value of money and how to use it wisely.

We mutually agreed that one hour of work should be rewarded with $1. Not that he knew much about the value of $1, but we closed the deal. That the work he can do is: to learn the numbers, learn the letters, learn songs, make something from Lego blocks, and draw and paint. Keeping his toys neat was a challenging topic. I won the argument, but it was not easy. His toys are his duty, and he will not be paid to keep them in their place.

As soon as Adam earned money, he purchased a toy. A bad and cheap one. The one he could afford for a couple of bucks. The same thing happened a few more times in a row. I was becoming frustrated, but I let him do what he wanted with his money. A few weeks later, I found him unwilling to “work” that day. The day after was the same. He argued that he is becoming “smarter” (his words), but he does not see anything improving with that and that he is earning his own money. He concluded that he has fewer toys now than before. He accused me that I had tricked him. Good point.

As usual, we went to the mall. Adam was unenthusiastic, and I feared my experiment would fail after a few good weeks. Suddenly, he asked how much time he needed to earn for some small dinosaur robot he liked. My answer devastated him. He will need an entire month to make enough money for that toy. It was too much for a four-year kid. We went home, and I was discussing with my wife whether we should buy him that toy anyway, despite my agreement with him. We decided not to push this too seriously and to surprise him next weekend.

And that would be the end of my experiment if it wasn’t for Adam coming to us the day after with a firm statement. He “will not spend money he is earning on toys he is not playing with and will try to save until he has enough for the robot dinosaur.”

Soon, I needed to dedicate one part of my wallet to his money, and he regularly checked if I was spending it. He started to do simple math and insisted that drawing and writing numbers with chalk on the street still counted as work. Less than a month later, he had his dinosaur.

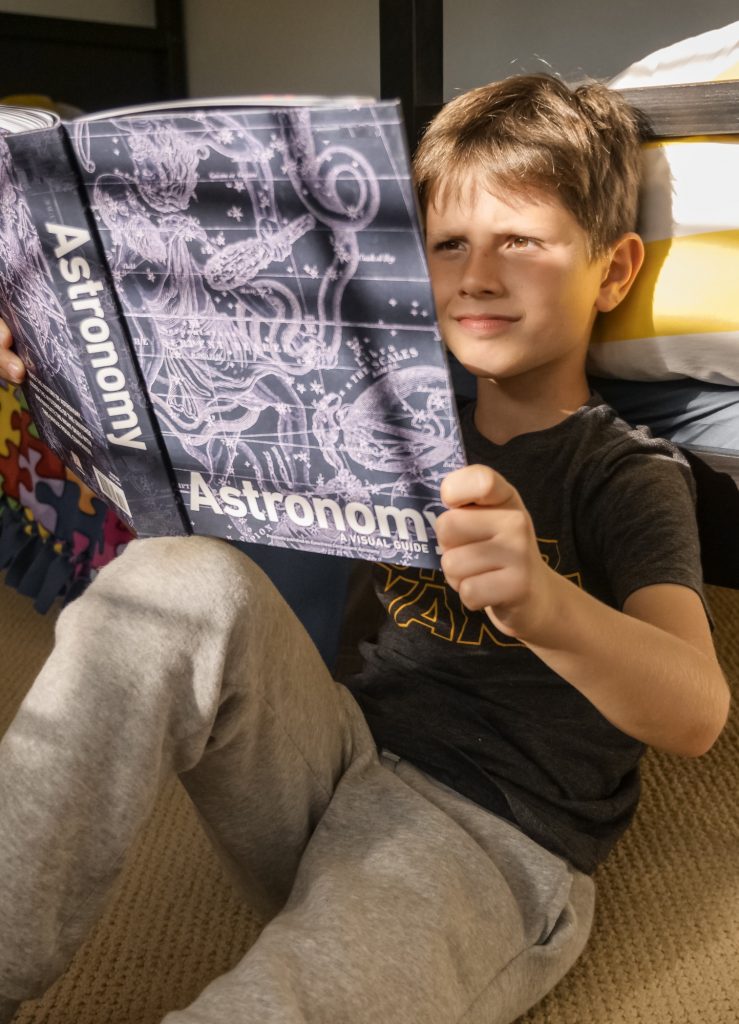

A bit more than a year forward. My now five-year kid was good in math and could easily do addition and subtraction with two-digit numbers. He finished reading his first book, “Young witch” (with big letters and simple sentences).

I needed to introduce special rewards for the completed books, which motivated him to start and finish more reading.

One more year forward. Adam was six years old.

He carefully selected the toys he was buying. He looked for their quality and determined how much he would play with them: Nerf guns, robots, a small microscope, action-reaction sets, a diving mask. Not all the purchased toys have been a success story, but most of them have.

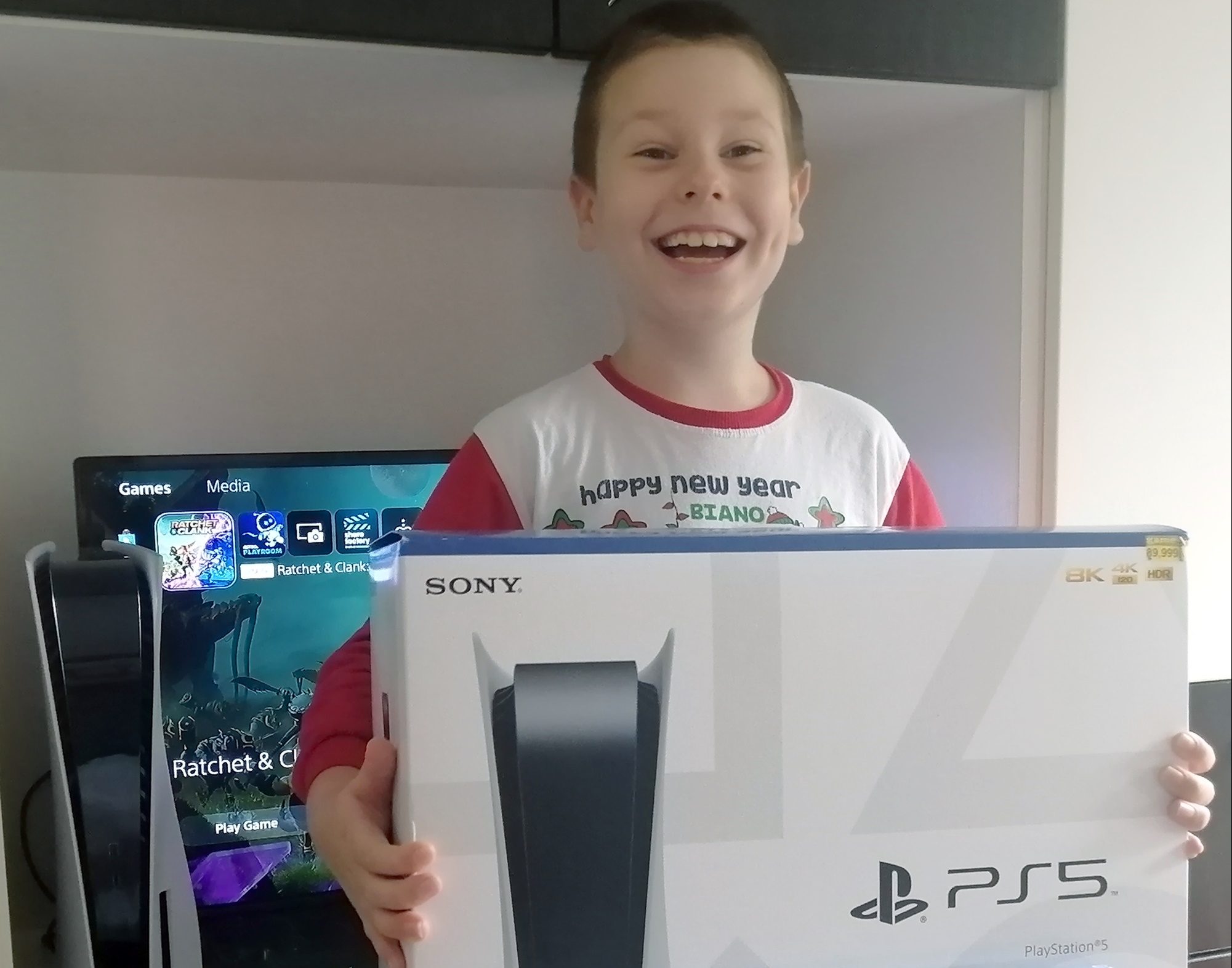

Two more years forward. Adam’s 8th birthday. The biggest challenge so far. Eight months ago, he decided he wanted to have Sony PlayStation 5. He was firm that he would spend no money until his birthday, but by his calculations, he could earn only half of the money needed to get SPS5, two joysticks, and five games. That was a lot of money for an eight-year-old to make. He asked for help and suggestions on how he could achieve his goal.

In the end, we agreed. Suppose he manages to be disciplined and earn half the money needed without spending anything until his birthday (for 8 months). In that case, I will give the rest of the funds required.

My wife and I have been curious if our son will manage this through. It was usual for us now that he earns and saves his money for a couple of months to buy things he likes. But to do that for eight months? Not to spend anything and at the same time to have more money than ever? We agreed to add more money if he is close enough to reach his goal. The main thing for us was to see how our seven-year-old is resolved and dedicated to getting what he wants on his own.

Long story short. His birthday is in a few days from now. Last night we were looking at which games to buy the first. The goal has been achieved. Adam made it.

It wasn’t easy all the time. He had periods of a week or more without doing anything about it. At some point, he was fed up with everything and was considering buying a cheaper but good enough gaming console. But, each time, Adam returned with new enthusiasm and energy, and yesterday he achieved his goal. There are no words for me to describe how proud dad I am now.

My conclusions on the topics:

Should you give your children pocket money, or should they start earning their money?

Kids should start earning money.

Kids should grasp what it takes to earn money and understand its value. This process will teach them that reaching specific goals requires patience and effort—some of the most critical life lessons. Dad should be a teacher, full of patience, and a guide in this process.

At what age should kids start earning money, why, how, for how long, and how much?

In my personal experience, kids should start earning money as early as possible. At the age of 3 to 5, they can fully understand some basic things such as: “Do this – get that as a reward” or “If you want something, do something about it.”

Learning these essential life skills will put children on the path to a better understanding of how the world surrounding them works and be better prepared for it. Kids at that age are fully capable of this if you just let them try it and be supportive and patient. It’s just skill, as anything else.

Should kids be pushed to earn their money?

Absolutely not. Dad should be there to support them as much as needed. It is one of the dad’s fundamental roles. Kids should become independent with time. Dads teaching their kids early on the value of money, planning, necessary skills, and patience are helping them become resourceful, independent, and proactive. Dad is helping his children from an early age to implement this. After 15-20 years of applying this, kids thought these skills would be independent and goal-oriented from an early age. You will not need to push them. It will come as a natural part of their development.

Should I encourage my child not to give up?

You should, but the child should not feel forced.

A kind and simple reminder are good enough. Remember children should be encouraged and positively reminded about the benefits of their efforts. Nothing more than that. Let them be if they are not in the mood to do anything that day or the entire week. They will have a whole life to work hard.

Talk positively. Give children ideas about what they can achieve in the short or medium term. Mention, all the best singers, actors, sports, and business people need years of hard work to be who they are and get what they possess now. Please don’t overdo it. If you do, your efforts will become a child’s burden and have a countereffect. You do not wish to become boring to children. Please encourage them to act once or twice per day. Friendly and with just a few words. It is enough.

They will work hard to get it when they get an idea of what they would like to have next. Dad then has to support them, give them achievable tasks/errands, and provide evidence of their progress and how good they are becoming (in reading, writing, math, drawing, playing an instrument, programming…).

Prove them that their work, consistency, and effort will get them tangible results and reasons to work hard. Compare together the results they had half a year ago: how much time they needed to read a page, their drawings, how good they play chess, and others.

Kids, teenagers, and young adults are you tired of your annoying parents? Are you annoyed by being always conditioned to do something you don’t like to get some pocket money?

Act now! Start working! Get your own money. Do it while you still have great ideas and a lot of energy. Do it before “the system” puts you in your place. Earn your money, and don’t be dependent on anyone. Show everyone that you can and that you have in you what it takes to be great. You will fail a lot of times, but at a young age, it is easier to get up and move on until you succeed.

Success or excuses? The choice is only yours.

If you have parents to support you, grab that opportunity. While they provide you with everything for living, make your success. Have fun, but don’t waste your time.